![]() One of the perennial problems of teaching intro physics is getting students to do their homework, so I was very interested to see Andy Rundquist on Twitter post a link to a paper on the arxiv titled “How different incentives affect homework completion in introductory physics courses.” When I shared this with the rest of my department, though, I got a link to an even more interesting paper from the same group, on the effect that doing homework has on student performance. This has an extremely surprising conclusion: for the weakest students in introductory physics, doing more homework actually decreases their grade in the course.

One of the perennial problems of teaching intro physics is getting students to do their homework, so I was very interested to see Andy Rundquist on Twitter post a link to a paper on the arxiv titled “How different incentives affect homework completion in introductory physics courses.” When I shared this with the rest of my department, though, I got a link to an even more interesting paper from the same group, on the effect that doing homework has on student performance. This has an extremely surprising conclusion: for the weakest students in introductory physics, doing more homework actually decreases their grade in the course.

This is surprising enough to be worth a little discussion on the blog, so we’ll give this the Q&A treatment.

See! I told you, homework is evil! And these people have proved it with SCIENCE! OK, let’s not get ahead of ourselves, here. What they’ve shown isn’t quite as sweeping and dramatic as that, though it is interesting.

Killjoy. OK, what did they actually show? Well, they looked at a very large sample of students in the second term of introductory physics– a couple of years worth of classes with around 1000 students/year– and looked at the correlation between the amount of homework those students did and their scores on the exams for the course. They first separated the students into four groups based on “physics aptitude,” though, and looked at each group independently. For the highest-aptitude group, they found what you would expect: students who did more homework got higher scores on the exams. In the lowest-aptitude group, though, they found the opposite: students who did more homework got lower exam scores.

That’s… weird. But how do you sort students by aptitude in the first place? I mean, how do you know which students are good at physics before they take the exams? The aptitude sorting is based on grades in prerequisite classes. The specific course they looked at was the second term of intro physics, covering electricity and magnetism. Students taking that course needed to take two calculus courses and the first term of intro physics first, and the average grade in those three courses was the basis for the “aptitude” sorting. This average was reasonably well correlated with the grade in the second term of physics, and also with other measures of aptitude (SAT scores, conceptual test scores, etc.).

Couldn’t that just be a measure of general student skills, though? That is, students who get lousy grades in calculus also get lousy grades in physics because they have poor study skills in both? That’s one of the weaknesses, yes. If it were just a measure of poor attitude, though, you might expect the “low-aptitude” students to all blow off the homework, and that’s not what they see– the homework completion rates for all the groups are pretty similar. These appear to be students who are putting a reasonable amount of effort into the class, and just not doing well.

Speaking of which, shouldn’t you show us these results? You could look in the paper, you know.

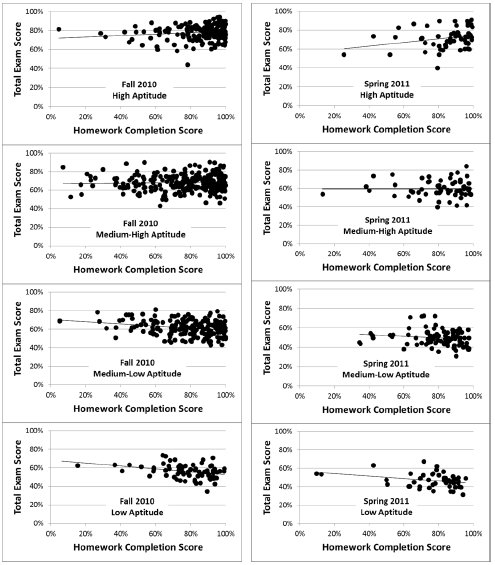

Yeah, but then I’d have to click the mouse button two whole times. Just put a graph in the post, please? Fine, here you go:

This shows the cumulative exam score (three midterms and a final) on the vertical axis, with the percentage of the homework completed on the horizontal axis. The high-aptitude group is at the top, and the low-aptitude group is at the bottom.

Those points are kind of scattered all over the place, dude. Yeah, but that’s pretty good for social-science type data. And you can see a pretty clear trend indicated by the straight lines on each of those graphs. For the high-aptitude group, the line slopes up and to the right, indicating the more homework is correlated with a higher grade. In the low-aptitude group, the line slopes down and to the right, indicating that more homework is correlated with a lower grade.

How big an effect are we talking? Not all that big– very roughly, doing an additional 10% of the homework raised or lowered the exam total by about 2%. But it’s statistically significant, and the difference between groups is surprising.

Yeah, that’s definitely weird. What would cause that, or is this one of those “correlation is not causation” situations? Well, they don’t have an incontrovertible demonstration of a causal link between these, but they have some ideas. The education-jargon term for it is that doing more homework “placed an excessive cognitive load on low aptitude students.”

So,…. basically, “Mr. Osborne, my brain is full”? Not quite as pejorative as that, but yeah. The idea is that students who don’t have a solid framework for doing physics end up inventing ad hoc “schemas” for each homework problem they do, idiosyncratic ways of explaining how they got the answer. The more homework they do, the more of these they accumulate, and it becomes hard to sort out what, exactly, they’re supposed to be doing.

The higher-aptitude students, on the other hand, are in a better position to interpret the problems in terms of a smaller number of universal rules, and thus have an easier time keeping everything straight. When they confront a problem, they have a smaller set of more flexible tools to draw from, so finding the right approach is easier.

It’s a nice story, but is there any other suport for it? Sort of. They looked at each of the mid-term exams separately, and the correlation between doing the homework for the relevant section and the score on that exam (so, graphs like the above only plotting the grade on the first quarter of the class versus the percentage of the first quarter of the homework done, etc.). On the first couple of exams, the low-aptitude groups didn’t show much correlation between grades and homework at all, but on the third exam and the final, the negative correlation was very clear.

And how does that help anything? Well, the idea is that for the first few exams in intro E&M, they’re only dealing with electric fields, and the number of techniques that can come into play is very small. In the third quarter, they introduce magnetic fields, which follow different rules. In the “excessive cognitive load” picture, this introduces a problem because the low-aptitude students can get confused between electric and magnetic field approaches. There’s a significant increase in the number of techniques they need to know and use, and that triggers the “negative benefit” of doing more homework.

Couldn’t it just be that magnetic fields are harder to deal with? I mean, there’s all those cross products and stuff… That’s also a possibility. That probably wouldn’t produce a negative correlation with homework, though– if anything, you’d expect students to get better with practice.

Which brings up another thing: What does this mean for teaching? Should you stop making weak students do homework? That’s one of the frustrating things about this paper (and a lot of education research, for that matter)– they identify a problem, but don’t do much to suggest solutions. They do note that this finding seems to run counter to the usual advice– most of the time, we tell students who are struggling to do more homework, not less– but it’s kind of hard to tell what to do instead. To be fair, though, this is a surprising enough result that it’s worth publishing even without a suggested solution.

But is this going to change your approach? Not immediately. For one thing, the effect isn’t all that big, and I’d want to see it confirmed by somebody else. More than that, though, I’m not entirely sure that this is broadly applicable.

Why not? Well, this is a study based at the Air Force Academy, where all entering students are required to take two terms of physics. This includes the 40-ish percent of them who go on to major in non-scientific subjects.

While this is great from a sample size perspective– they’re teaching 1000 students a year in intro physics, so it’s easy to get statistical power in only a few years of testing– it might mean that their sample doesn’t generalize. Their lowest tier of physics aptitude is going to include a bunch of non-scientists who probably wouldn’t take physics at all at most other schools. The students I see in Union’s intro classes might not include any from the population showing the strongest negative effect in this study.

So, in the end, I think this is probably saying something interesting about the way students learn physics, but might not have that much practical application. Then again, a different approach to homework that turned the negative correlation around for the weakest students might well produce a dramatic improvement in the stronger students, as well. Which would be worthwhile.

As there isn’t any such approach on offer yet, though, I’m going to hold off on making changes until somebody suggests one. This is definitely something to keep an eye on, though.

And, as a nice bonus, it’s a great excuse for not doing my physics homework! I’m making a rational strategic decision to improve my grade! Well, as long as you’re happy with thinking of yourself as a low-aptitude student, that is.

Oh, yeah. Good point. I guess my ego does demand that I do my homework, after all. Vanity: a powerful force for good. In physics education, anyway…

F. J. Kontur, & N. B. Terry (2013). The benefits of completing homework for students with different

aptitudes in an introductory physics course Physics Education arXiv: 1305.2213v1

Hmm. Will it help my grade if I turn this paper in with my E&M final on Wednesday?

It seems to me that the interpretation could also be that overall, the amount of homework done does not affect the grade distribution for the course, seeing as all the graphs look like they could be subsets of the Fall 2010 Medium-high aptitude graph. Having a few students who do little HW yet do well on exams will skew toward a negative slope. Without those students you get a flat or positive slope. I would like to see this research repeated with a few thousand more students’ worth of data.

Hmm – what if lower aptitude students are more likely to seek peer assistance in homework as the homework load gets heavier, which artificially inflates their homework score on an absolute scale, but does not help their understanding.

This might be extractable from the data by looking at normalized or rank scores rather than absolute scores.

This is no surprise. If you want to get the weaker students to do better using homework/quizzes, you put them into study groups with stronger students. The peer tutoring method work shows that that works, and the AFA is an ideal place to do it because you can force everyone to show up.

Otherwise, the homework merely reinforces the bad models that the weaker students are using to try and understand the work.

It would be interesting to try a similar study with a state university that has a large, strong engineering program (Michigan and Purdue are two examples that come to mind). That will at least test the objection that the weakest students might be people who would not ordinarily take physics.

Also, the Air Force Academy is not the only university that requires physics of all of its undergraduates regardless of major. (My undergraduate degree is from such a university.) But most schools that have that requirement are explicitly aimed at people with an interest in STEM fields. The Air Force Academy probably draws more than a few wannabe pilots. Whether this trend holds for people at a school like, e.g., RPI, would also be a check on whether the lack of self-selection for STEM interest explains the Air Force Academy results.

Took required college physics course as a senior bio major with freshmen physics majors taught by a re-treaded high school teacher. Had the highest exam average in the class, but got a B because I didn’t do all the highly repetitious homework problems. Learned an important lesson: don’t teach science like that.

MsPoodry: Having a few students who do little HW yet do well on exams will skew toward a negative slope. Without those students you get a flat or positive slope. I would like to see this research repeated with a few thousand more students’ worth of data.

They talk about a test where they excluded the outliers, and found a similar slope (though now I don’t recall whether that was just the high-homework-completion outliers, or the low end as well). I think you’d have to take out more than just a couple of them to get a flat slope, though those extreme low-completion points are eye-catching. I definitely agree about the need for more data, which they’re presumably working on…

Steinn: Hmm – what if lower aptitude students are more likely to seek peer assistance in homework as the homework load gets heavier, which artificially inflates their homework score on an absolute scale, but does not help their understanding.

These are completion percentages, not scores, I believe. That is, it’s the fraction of the homework they did, not the fraction they got correct. (Though the axis label is a little ambiguous…)

Also, they talk about checking to see if cheating was an issue, using a time-per-problem standard as is fairly common in this field, and say they didn’t see any evidence of cheating on a broad scale. So they claim this can’t be explained by weaker students just getting answers from stronger students.

On the general findings, I should also add that while the result is kind of surprising, anecdotally, I’ve definitely had a number of students who dilligently do homework and practice problems and come to office hours, and seem to only confuse themselves more as a result. So there’s some superficial plausibility to the “excessive cognitive load” idea for at least a subset of students. How to help them, though, remains kind of mysterious.

Isn’t there a selection bias issue here? Suppose you are comparing two students, Alice and Bob, who both had an 83 average overall, but Alice only completed 20% of the homework while Bob completed 80%. Of course you’d expect Alice’s exam score to be higher. It doesn’t necessarily have to be, but the only alternative is for Bob to be doing utterly terribly on his homework. I’m confident that if you condition on final grades, exam scores and homework completion will be negatively correlated, but this tells us nothing about whether homework is valuable.

Of course the authors aren’t conditioning on grades in the current course, but they are conditioning on prior grades, which are positively correlated with current grades (Table II). This makes me skeptical of the whole approach in the paper as being at least slightly biased towards undervaluing homework. Determining how biased it is would take a more detailed analysis.

Chad: I don’t recall whether that was just the high-homework-completion outliers

It’s specifically the high end: “students who scored above 90% on homework completion are removed from the analysis” The reason for this was “Additional inquiry revealed that that subset of students achieved their high homework scores by copying solutions from the Internet.”

I second MsPoodry’s concern – due to lever arm effects and the squared deviation penalty, a few widely scattered x-axis outliers are going to have a disproportionate effect on the value of the slope. That said, there still looks to be a trend when you cover them up. I’m not sure if it’s still statistically significant, though.

Regarding what to do, if the cause actually is cognitive overload, the straightforward way is to encourage the confused student to throw out all their old baggage and relearn with a new and appropriate mental framework. (Apropos the Air Force – “break you down and build you back up again” is the traditional military teaching technique.) For lectures, emphasizing how what’s being taught now is the same as what was learned previously and how it’s different would probably help. From my experience, professors tended to have the attitude that once you’ve had the exam you’ve mastered the material, and revisiting how it fits in with new material was unnecessary.

Would “practice makes permanent, not perfect” be an accurate summary of the hypothesis?

@Chad: I think “homework completion” has to mean “completed correctly” – otherwise the completion fraction ought to crowd the 100% axis more strongly.

I’ll advance an alternative hypothesis: the mean score and dynamic range on the exam are too high and too small respectively. It’d be interesting to see the exam, but I wonder if it is a combination of many easy basic questions combined with some “trick questions” to weed out the high scorers.

That would explain the anti-correlation also.

Steinn: I think “homework completion” has to mean “completed correctly” – otherwise the completion fraction ought to crowd the 100% axis more strongly.

It’s really not clear what they mean by “completion score” here. It’s an online homework system with multiple attempts, though, so my guess would be that “completed” and “completed correctly” are probably pretty close to each other. Based on their other paper, I think those percentages may be just the fraction of assignments that a student does at all.

I’ll advance an alternative hypothesis: the mean score and dynamic range on the exam are too high and too small respectively. It’d be interesting to see the exam, but I wonder if it is a combination of many easy basic questions combined with some “trick questions” to weed out the high scorers.

They give a detailed description of the exams, which were apparently written by the PER group in consultation with the course instructors. So, maybe.

Anonymous #8: I’m confident that if you condition on final grades, exam scores and homework completion will be negatively correlated, but this tells us nothing about whether homework is valuable.

The negative effect on grades from selecting on prior scores ought to be pretty small, as homework is a very small component of the final grade– not more than 10% in any of the sections they looked at. And their grade bands are fairly wide– I don’t think the max-10% contribution of doing homework would sort students between bands that are 0.75 of a grade point wide. But then, the effect they see is small, and it might be enough to make a difference.

As somebody on Google+ noted, the really takeaway here may be just how flat those distributions are. Whether the slopes are real or not, homework appears to make almost no difference to exam scores, and that’s a little surprising.

Here is an alternative interpretation of people who are not doing well and not benefiting from practice: maybe they should not be in STEM. Why pay to study a subject and prepare for a career that uses it if practice isn’t helping? They are probably smart students who will do great majoring in something else and be great USAF officers, they just shouldn’t be on the STEM track. Maybe the class doesn’t need to be changed because it is doing exactly what it should be doing.

Chad,

Thanks for posting on our article. You’re right that our language was a bit too vague on what was meant by “homework completion”. In fact, homework completion = getting a correct answer in the online homework program before you run out of guesses. We’re still research (1) what the underlying cause of this effect is, and (2) how to reverse it, but, as of now, we haven’t come up with anything definitive, which is why we didn’t try to offer solutions.

Chad,

Thanks for posting on our article. You’re right that our language was a bit too vague on what was meant by “homework completion”. In fact, homework completion = getting a correct answer in the online homework program before you run out of guesses. We’re still researching (1) what the underlying cause of this effect is, and (2) how to reverse it, but, as of now, we haven’t come up with anything definitive, which is why we didn’t try to offer solutions.

Alex-

Students don’t pay tuition at the Air Force Academy.

Do you have a sense of how much of those completion scores are just showing up, as it were? My experience with online homework systems with multiple attempts is that students tend to get the right answer within five trials in 80-90% of the problems they bother doing. That is, If I have a student who got 50% of the homework points, that’s generally because they only attempted 60% of the problems, and blew the rest off.

Chad-

I think your intuition is correct. We are currently looking at how the number of wrong attempts connects to the other data that we’ve looked at, but, from my experience, if students attempt to do homework problems and are given 3-5 attempts to get it correct, they will almost always get the points.

Your style explaining modern physics reminds me the great R.P. Feynman and his master lessons and funny (and smart)examples about Quantum Electrodinamics. Seriously Mr Orzel, congratulations for your amazing books.

Alex @13: You may have overlooked the note in the original post that passing the course in question is an Academy-wide requirement, even for people who aren’t STEM majors. You might ask why they should require it, but given the nature of what the Air Force does, the requirement does not surprise me. I don’t know what fraction of USAFA cadets are in non-STEM majors, but I suspect it is smaller than West Point or Annapolis, based on a sense that the Army and the Navy have greater need for non-STEM majors (e.g., language experts for translation/diplomacy/liaison) and the fact that the Air Force was part of the Army until the late 1940s (the split occurred around the time the War and Navy Departments were consolidated into the DoD we know today).

Awww, too bad I just finished teaching about linear regression, this would have been a great paper to discuss in class!

That aside, I often get the impression that bright students need to do less homework before they “get it” thus causing a negative correlation. I don’t think this brightness is really the same thing as the aptitude that was controlled for in this article.

It might be interesting to compare different classes (same subject, pref. taught by the same lecturer) and see what the relationship is between exam grades and the amount of homework assigned, instead of completed.

Those correlations look very poor.

What are the t scores on those coefficients?

Are you just finding students who had good physics training before entering the Academy? Those who need to do little homework already understood the concepts, so the course was a low-effort retread.

I suppose that this could be picking out those with good backgrounds but bad attitudes, who coast on their high-school preparation and get good-but-not-great grades putting them in the upper end of the lower grade bands.

However, I don’t think that’s all that likely. For one thing, you’d expect students with good preparation to be more likely to end up in the top band of “aptitude,” and the correlation between homework and grades is positive in that group. Students who put in less effort there get lower grades.

More than that, though, this is the second course, on E&M, and there’s a much bigger jump between high school physics and college level physics in E&M than in mechanics. Anecdotally, while I regularly see students in intro mechanics coast on their high school achievements and get good grades, those who attempt the same trick in E&M generally get crushed. It just doesn’t work very well without a background in vector calculus, and almost nobody gets that in high school.

Eric,

I get that the course is an Academy-wide requirement, and I get why they require it. My point is that by identifying a subset that is not benefiting from practice, this course is probably performing a valuable role. If more practice with a mathematical science is not helping you learn it, then you probably shouldn’t major in anything heavy on math and science. It is fine that the Academy requires everybody to study physics, I just wonder what lessons people should draw from what happens when they study it.

And yes, it was clumsy of me to refer to spending money. I was thinking of some more general lessons about studying STEM, and what we might conclude if this finding were replicated elsewhere. If it were replicated elsewhere, it would suggest to me that the subset of students that doesn’t benefit from practice is probably the subset that should change majors sooner rather than later.

And even in the context of a zero-tuition institution, students are still investing time, and if they aren’t doing well in the subject they’d do well to invest their time in a subject where they can be more successful, some subject where that success might have value in their subsequent careers.

Do the weaker students know by now that they are unlikely to fail? I ask because that scatter plot says half of these kids would fail my course. Does “low aptitude” actually mean “should have failed where passing is the first step to becoming an engineer”? I ask because my experience is that a student who has learned how to study in the process of passing the first semester has a very high probability of passing the second semester unless they flake out.

Some other thoughts:

1) I find that getting less than 80% of the HW correct in my classes is a sign of the end times. Ditto for getting 100% by copying or being told the formula to use.

2) I also find that the second semester is unique in several respects. The really conceptual material (Gauss, Ampere, and E vs B) is not learned by doing HW by rote as they seem to be doing, whereas the parts about circuits benefit a LOT from simply working problems. First semester does not have this sort of variation in the type of studying needed at various points in the semester.

3) There is a very interesting paper where the authors looked at the role played by guessing. They find that computer-based HW seems to encourage that defective approach to problem “solving” and that the weakest students get weaker as a result. I’ve seen this group grow over time as computer-based HW has been adopted across a wide swath of the STEM curriculum and this might be what they are actually seeing.

4) The problem of confusing E and B strikes me as similar to the way students confuse derivatives and integrals. My attack on it is to assign some E problems along with the B problems. (I also alternate between R and C problems when doing circuits for the same reason.)

Alex – Thanks for the clarification. Incidentally, one of my hopes is that better addressing the needs of hard-working physics students who, nevertheless, struggle can save a lot of money and heartache on the part of both students and educators. Though the money issue isn’t present at the Academy, the heartache can certainly occur.

CCPhysicist – Are you referring to Pascarella’s article (The Influence in Web-Based Homework on Quantitative Problem-Solving in a University Physics Class)? We do reference that in our article. Pascarella’s article is one of the few to suggest some negative impacts of online homework. I think in general, you bring up a lot of good points. Some of the feedback that we’ve gotten on our article is that everyone knows that simply getting points in an online homework system will lead to learning. I tend to agree with that sentiment. But the issue is, what aspect(s) of homework does lead to learning? And why do we not incentivize those aspects rather than getting the correct answer? Your comments about mixing together problems also gibes with another favorite paper of mine from a pair of educational psychologists on the benefits of “interleaving” homework problems – “Recent Research on Human Learning Challenges Conventional Instructional Strategies” by Rohrer and Pashler (2010).

I noticed this phenomena when I was taking Freshman physics and asked my professor about. His hypothesis was that those with high aptitude did all the homework to enhance their knowledge while those with low aptitude did all the homework because they knew they would not do well on exams and they wanted to maximize what credit they could. Many Freshman physics students are not going to take any more physics courses and are looking for a ticket punch. They often just want a ticket punch and get past the ordeal. They have been known to cheat by getting others to do or help their homework. But simply put, the motivations are different. I have always found the hypothesis to be tenable since.

Yes, I was referring to the Pescarella article. (I wish I knew what the mystery college was for that study, and what instructor effect there might be. IME the instructor effect is not small.) My hypothesis for the cause is under active challenge each semester, but there is also a student effect. I think one of my classes did better than another simply because one student asked “Yahoo answers told me how to do it, but I don’t understand why I had to add an extra factor of 2 to their formula?” early in the semester. I think I replied that I was glad he asked, because Yahoo answers isn’t taking the tests and I will give less than half of the possible points if all you do is use some magic equation.

I love the “ticket punch” comment. Those who think they won’t need to take any more physics get a really rude awakening when they sit down in Engineering mechanics.

PS to Fred Kontur – I’ve had History and English majors in my physics class who were on their way to fly jets (Navy or AF) so I appreciate the challenge at the Academy, although in my experience those kids work harder than anyone except a Marine.

Interesting, but I’m not sure what – if any – meaning to attach to it.

One of the troubling aspects is whether the selection into “aptitude” groups is the origin of the negative slope for the “low aptitude” group. If we assume that grades are consistent from class to class for a given student, then the selection process for “low aptitude” students is simply selecting for students with low grades. Obviously if you pre-select for low grades, then any student in that group who has high exam grades must have low homework grade (otherwise their grade for the class wouldn’t be low), and vice versa.

Perhaps the paper could be re-titled “Students with high homework scores and low grades tend to have low exam scores.” But that would be less sexy.

Anonymous Coward –

I think Chad covers your criticism somewhat in #12. I should also point out that homework is not a part of the overall course grade in the Calculus 1 and 2 classes at USAFA. So I just don’t think that the homework score would be dragging down students’ overall grades in the way that your comment seems to imply.

Fred Kontur (#31) –

Thank you very much for the clarification! I am grateful for the honor of receiving feedback from an author of the study.

That information certainly weakens the role my explanation would play in the negative slopes, but if homework is part of the score in one of the three classes used to classify aptitude (and the second term physics class) then I think my point would still partially stand, no?

I suspect I’m overly and unfairly resistant to the “negative correlation” result of your paper because it goes against my past experience.

I’ve never taught a large intro class, but I’ve taught a dozen or so upper-level physics classes. At the end of the semester I plot exam & final grades vs. homework grades (for fun and curiosity). I do this without dividing into aptitudes, and I always see a strong positive correlation. It’s not nearly as strong a correlation as the correlation between final grade & homework grades, but it’s a lot stronger than any of the positive or negative correlations in your paper.

Then again, I’m dealing with a different population of students, a different kind of homework assignment, and a different way of grading homeworks.

This research fits with other work which shows that setting challenging homework is less effective than setting homework which is either repetitive (of what has just been learned), rote learning (eg vocabulary) or preparatory (watch the video, read the chapter).

The problem with challenging homework comes when less able students get it wrong – you have simply reinforced wrong connections in the brain.

The part of the learning where having the teacher present is most effective is when students are trying something new.

Teachers may like to join The Evidence-Based Teachers Network. http://www.ebtn.org.uk/